Shipwreck Piece of Eight Pendants

Linked to the Longitude Pen project TMB has been involved with, I decided to offer an equally fascinating range of Piece of Eight Coin Pendants, mostly involving very rare coins raised from the Association wreck of 22nd October 1707, but a few others too. One thing’s for sure, if worn visibly be prepared for questions to be asked about these most intriguing of coins – and then you can enthral the questioner with the back story of your very unique pendant!

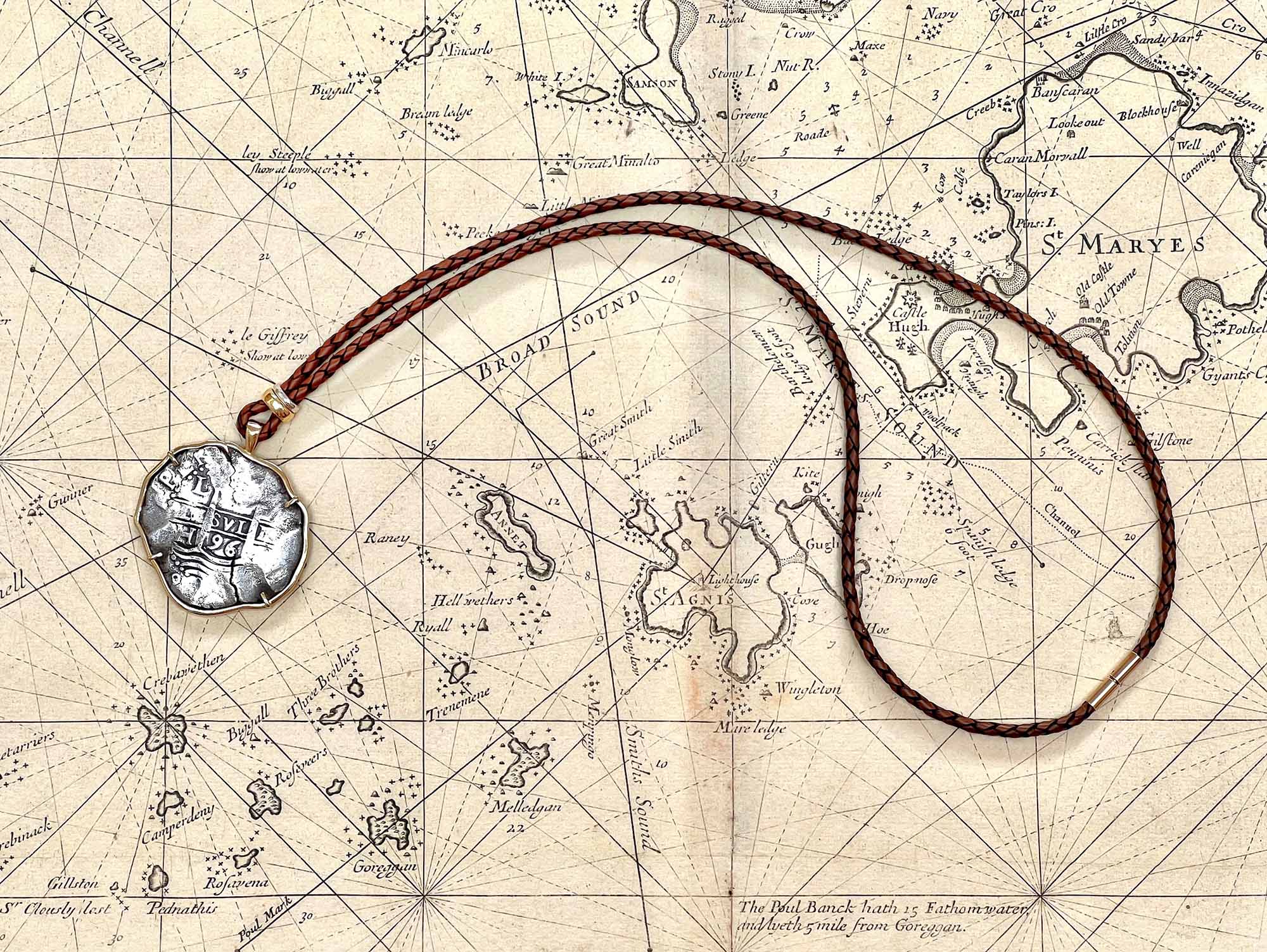

For many years I wore a pendant I’d had made using a rare and very historic silver piece of eight coin raised from the Association wreck.

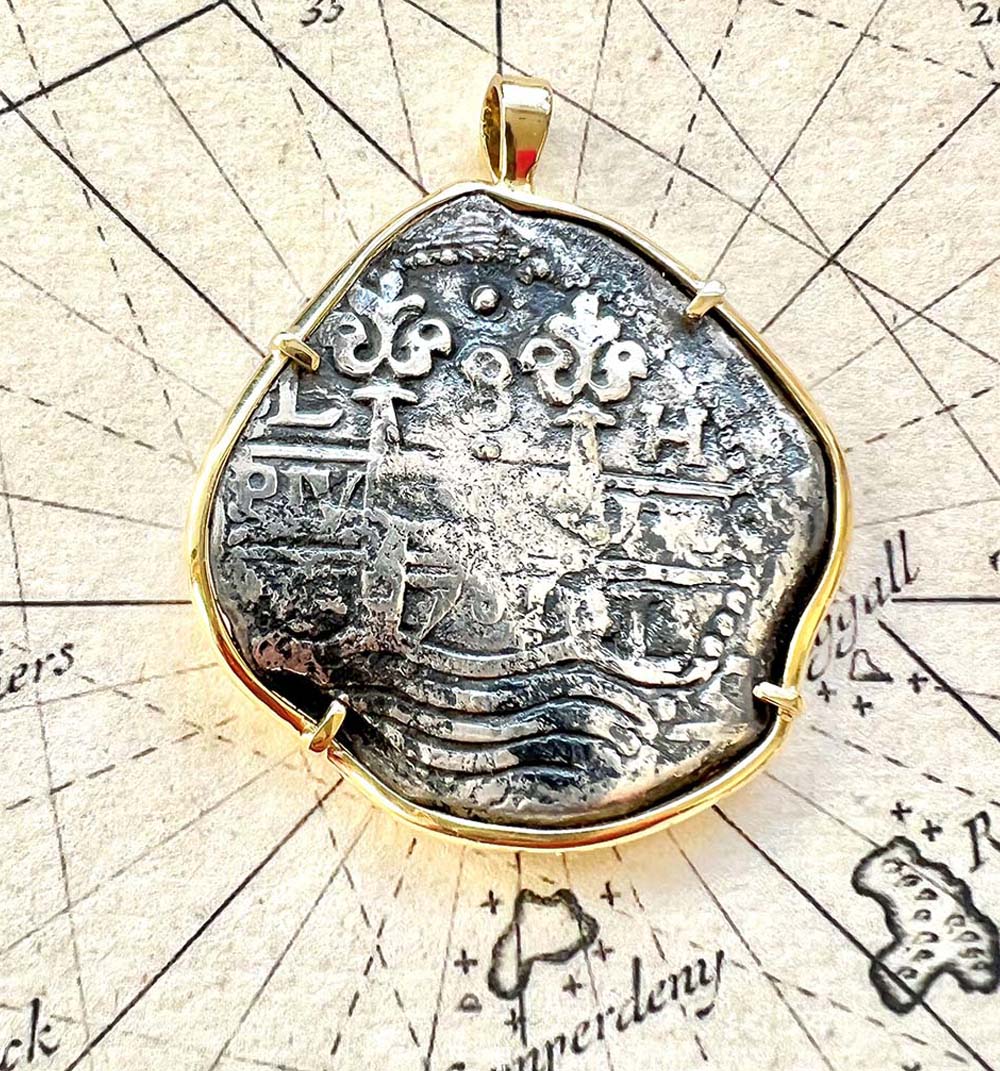

Recently, with the rekindling of interest in Association and the flagship’s back story, I decided to ‘upgrade’ it into something more visually exciting by commissioning a top London jeweller to fashion a custom 18ct gold bezel around it, the rich golden colour contrasting wonderfully with the silver coin within.

These coins are so unique, fascinating and attractive that I thought I’d create some pendants that others can acquire, should they wish too. Pieces of eight from Association are nowadays extremely scarce and hard to come by – and when they do come by their value is high, especially for good examples, so availability and choice is very limited.

With a couple of exceptions, the below are pieces of eight, so quite big, bold and weighty, especially with their chunky gold bezels.

Whether you decide to acquire or not, I hope you enjoy admiring these fascinating pieces of historic sculptural art, each and every one truly unique!

The Back Story

Whilst helping to design and create the Longitude Pen I was transported back to my youth and a fascination with shipwrecks and sunken treasure.

I’d always had an interest in finding lost pieces of history, be it fossils, fragments of Roman or medieval pottery, or WW2 relics (I got in trouble at primary school for bringing in a rusty dummy hand grenade I’d found in a local field to show my chums!).

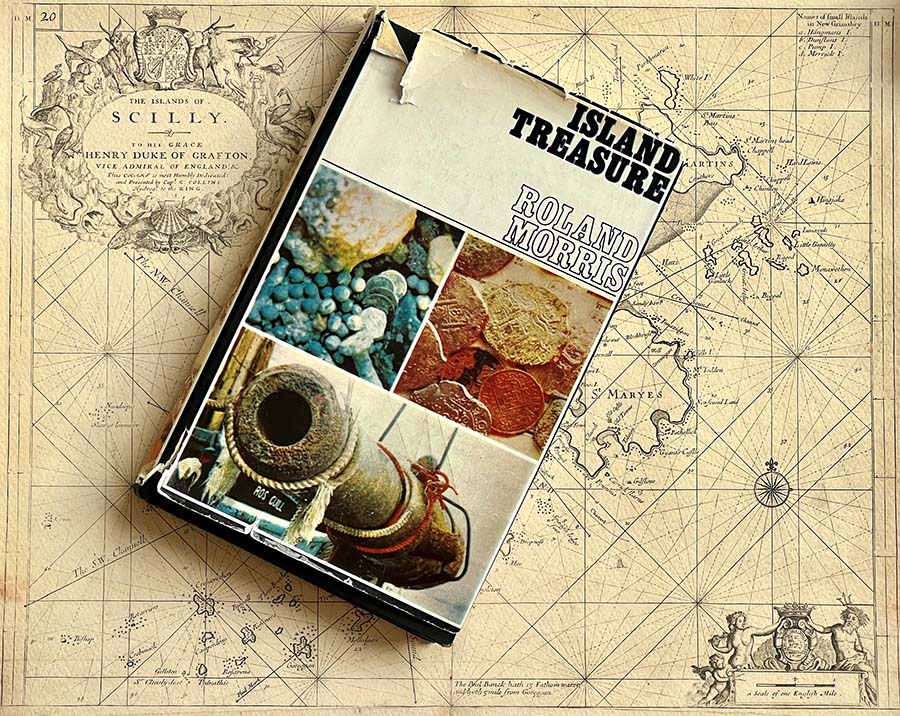

But pictures in magazines of artefacts raised from long lost galleons was on another level. As a teenager I read about the Association wreck on the Scillies and was grasped by the story, especially how they’d found bronze cannons and fabled pirate-lore pieces of eight, made famous by Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island’. I badgered my parents to go on holiday to Penzance so I could visit Roland Morris’s Museum of Nautical Art and his wonderous Admiral Benbow pub, both filled with intriguing shipwreck artefacts.

The Association, flagship of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, pictured early evening of 22 October 1707. Soon, in darkness, Association would founder, along with three other Royal Navy ships, upon the Western Rocks of the Isles of Scilly due to navigational error. In all some 1,450 men were lost that night, prompting Queen Anne’s government to form the Board of Longitude, ultimately leading to the creation of John Harrison’s life-saving marine chronometers.

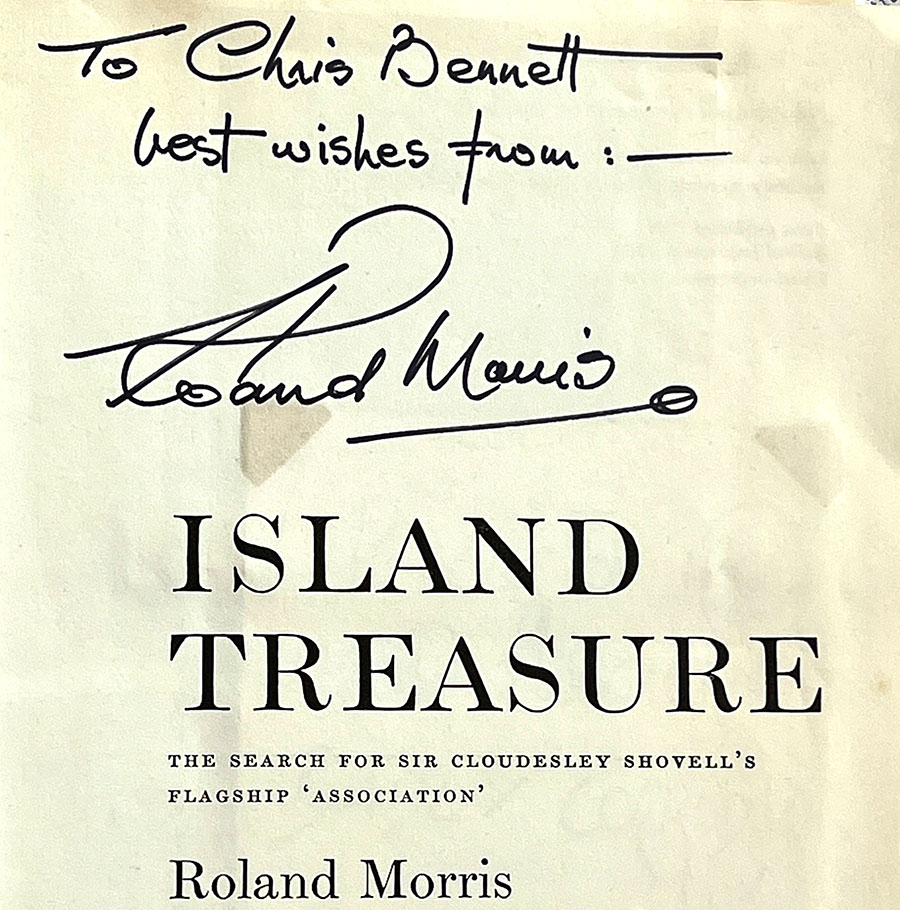

A long-time marine salvager and leader of a team working the Association site on the Gilstone Ledges of the Western Rocks since the wreck’s discovery in 1967, Roland Morris had become a bit of a celebrity in my mind. A high point of the holiday was meeting Mr Morris and obtaining a signed copy of his book, ‘Island Treasure’, in which he tells the story of Association, it’s finding, and artefacts recovered. How I admired the bronze cannons on display from the wreck, fascinating pieces of history.

At the end of the holiday, I persuaded my father to lend me some money so I could pay the £34 that Roland Morris asked for a good and rare silver Spanish piece of eight from Association. As a teenager £34 was a lot of money to me then, but this was an opportunity to acquire and possess an incredible piece of history, directly from the man himself! I treasured that coin and still have it – although many years ago it became a unique pendant. Over the ensuing years I acquired a few more Association coins from him too.

I myself did research into shipwrecks, with the dream of finding my own, most notably the El Gran Grin, one of the largest vessels in the iconic Spanish Armada, lost near Clare Island off the western coast of Ireland in 1588, and the 100 gun HMS Victory, forerunner of Nelson’s, believed lost on the Casquets off the Channel Islands in 1744. Sadly, neither project developed beyond paper and day dreams, although the Victory was discovered in 2008, complete with bronze cannons (but nowhere near the Casquets!), whilst El Gran Grin, flagship of Don Pedro de Mendoza, and undoubtedly richly laden, remains a treasure to be discovered.

Gradually my interest turned elsewhere, although not the passion for discovering and recovering history – that was to later manifest itself in the form of aviation archaeology, and a different type of wreck, crashed Battle of Britain 1940 aircraft. In 2004, following the discovery of the Hurricane aircraft beneath Buckingham Palace Road, this interest led to the creation of TMB Art Metal.

I never totally forgot about Association, but it was parked for decades until a couple of years ago, when I bought two heavy bronze pulley sheaves recovered from the wreck that once belonged to Roland Morris (now long deceased) from his Museum of Nautical Art. The acquisition of these led to the idea of the Longitude Pen linked to the loss of Association and rekindled my interest in the wreck. But it also rekindled my interest and fascination in pieces of eight!

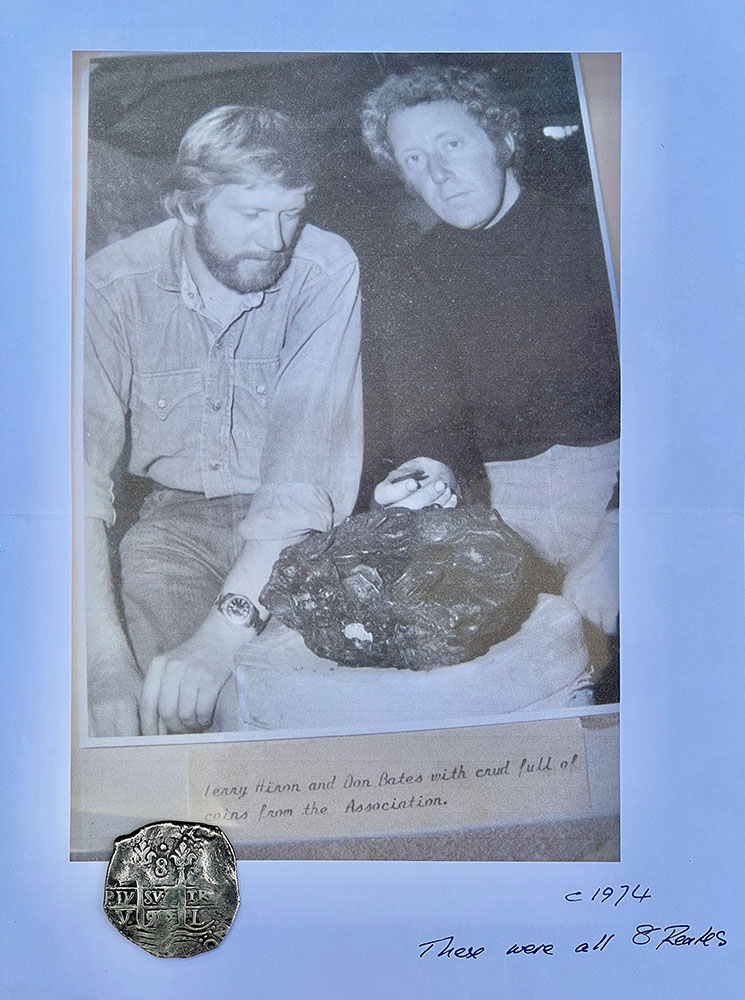

Jim Heslin and Terry Hiron, long-term salvors of the Association, with thousands of silver coins recovered from the shipwreck, the contents of a chest.

Thousands of coins were found at the Association site, mostly British, but many 8 reales too – the official name for a piece of eight. Nobody knows how many, as although finds were supposed to be reported to officials, many were squirreled away quietly by rogue divers. Apparently in the late 1960’s, the period when most material was recovered, they were even used as unofficial currency on Scilly – until their true monetary value was realised!

It’s now impossible to know why pieces of eight were aboard Association. It could’ve been international contingency money, it could’ve been merchant’s coins being carried for security (for a fee), or it could’ve been Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell’s own personal wealth. The bronze cannons found were mostly of French origin captured at the Battle of Vigo Bay in 1702, when a combined English and Dutch fleet, involving both the Association and Admiral Shovell, captured or destroyed Spanish and French ships within the bay. It’s very possible the Spanish coins came from there and remained aboard Association, which under Shovell was designated to help remove ‘booty’ from captured French and Spanish ships.

On 12th October 1702 a combined British and Dutch fleet captured or destroyed a Spanish treasure fleet that sheltered within Redondela harbour at Vigo Bay. Protection by a boom across the harbour entrance and by guns and French warships proved ineffectual. The 90-gun Association bombards and destroys a gun battery to the north side of the harbour, whilst in the background is seen the Dutch 92-gun Zeven Provincien. Having rammed and broken the boom, 80-gun Torbay was intercepted by a hastily rigged fireship, setting Torbay alight and then exploding next to her – the ship saved when the vessel’s cargo of snuff billowed up and settled back down on Torbay, snuffing out the fire!

The condition of the silver coins raised varies. Those loose on the seabed for the 260 years immersion are generally very corroded, but others that came from hoards (contents of chests) concreted together, protected within the ‘clump’ could be as good as when lost in 1707.

Part of a large clump of pieces of eight concreted together, probably by silver sulphide.

What is a Piece of Eight?

Officially Spanish 8 reale denomination, pieces of eight were truly international currency, welcomed everywhere. In the British Isles they were valued at 4 shillings and 9 pence (4/9), so 3 pence less than the British crown, which had a value of 5 shillings (5/-) – in 1707 a spending value of about £50. The 8 reale coin was the forerunner of the US dollar – ‘dollar’ simply the English spelling of the same size ‘thaler’ coins produced in the Spanish controlled Netherlands, the letters ‘th’ being pronounced as a ‘d’.

These are fascinating coins, each one unique, no two alike. In contrast to dull perfectly formed modern coinage, pieces of eight are characterful art forms with an intriguing story.

Made from silver mined by the Spanish in South America at Lima, Peru, and at Potosi, high in the Andes in present day Bolivia, the coins were manufactured by cutting blanks from cast bars of refined silver bullion, clipped to the requisite weight of 27 grams, heated and hand-hammered between crudely engraved dies, impressing the design onto both sides. Produced in volume and in haste, with little care to make them round, the uneven surface and irregular shape of the blanks prevented well defined strikes, so consequently the legends are frequently missing or only partially visible. Many coins were struck rapidly two or even three times, ending up with a disjointed or double image appearance. But the Spanish authorities were unconcerned with the shape of the coins or visible dates – the important features were the assayer’s mark and mint mark, as it guaranteed the fineness of the bullion and the correct weight. The penalty for not showing these marks was severe.

The only 8 reale coins that did bear the full design were termed ‘Royals’, made with special care to gift to dignitaries or to reward people for outstanding service. Attention was paid to ensure that the entire design was imprinted on the neat round blank – the result a work of art, so much so that many of these coins have a hole in them, worn as a pendant or medallion. Nowadays these coins fetch huge sums on the numismatic market.

But this crudeness in making is a significant part of these coins’ charm and fascination, no two in existence alike, each and every one unique.

Example of a carefully struck ‘Royal’ 8 reale presentation coin dating to 1670, which has been holed to wear as a pendant, as they often were. Even this carefully produced coin has been double struck on the pillar side.

They are also termed ‘cobs’, from a simplification of the Spanish phrase ‘cabo de barra’, made from end of bar. Although crude the coins were of very fine silver, the purity ranging from about 92% to 98% (modern sterling silver is 92.5%). This high purity is why the cobs were accepted in trade everywhere, as it was known that a piece of eight was literally worth its weight in silver. Because their value was in the metal of which they were made, not their ‘face value’, the coins could be cut into pieces of lesser value, hence the term ‘piece of eight’. That said, whilst the 8 reale was the biggest of the coins, there were also four, two, one and half reale coins too, each halving in weight and size.

In fact cobs weren’t only struck for use as coinage but also as a means for sending bullion in fixed quantities, easily divisible, back to Spain for repurposing. In consequence, a large proportion of cobs were remelted and for this reason, despite the vast quantities minted, were it not for sea-salvaged examples recovered from shipwrecks today cobs would be scarce – although even with the infusion of these coins, good examples remain rare and sought after by collectors.

Potosi and Lima coins adopted a ‘pillar and waves’ design in 1652 and 1684 respectively. If the mint mark is not visible in the upper left and lower right-hand corner you can distinguish between the two mints by the waves underneath the pillars. When the waves go down between the pillars the mint is Lima, if the waves go up the mint is Potosi. The pillars with crowns atop represent the Pillars of Hercules that stood on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar at the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, the waves representing the area beyond the pillars, the Atlantic Ocean where the New World was discovered by Spain. In the centre of the design are the letters, PLV-SVL-TRA – plus ultra, or ‘more beyond’, the message boasting that Spain had influence over most of the world, new and old.

Eventually the crude hand-struck process was replaced in 1732 with the screw press, eliminating the irregularly stamped pattern inherent to hand-held dies. The screw press was a technological leap which produced coins of consistent shape and quality. The blank of silver was set between two dies, then the top die was screwed down under great force, this process forming near-perfect coins with a milled edge.

A 1733 example of a screw press produced ‘pillar dollar’ piece of eight.

The value of these fascinating hand-made coins has rocketed over the past few decades. A good condition piece of eight from a famous wreck like Nuestra Señora de Atocha, lost off the Florida Keys in 1622 with an absolute fortune in gold and silver, can fetch several thousand dollars, and even poor examples well in excess of a thousand. Many of the gold doubloons, a golden version of an 8 reale coin, sell for tens of thousands. Their value is partly due to scarcity in the numismatic market, but also enhanced by the romantic swashbuckling back story of pirate treasure.

The Association of 1707 is one of only a very few wrecks around the British Isles from which 17th century Spanish-American pieces of eight have been recovered. Such coins rarely come on the market today, and when they do their values are considerably enhanced due to the link with this famous shipwreck and the story behind it.

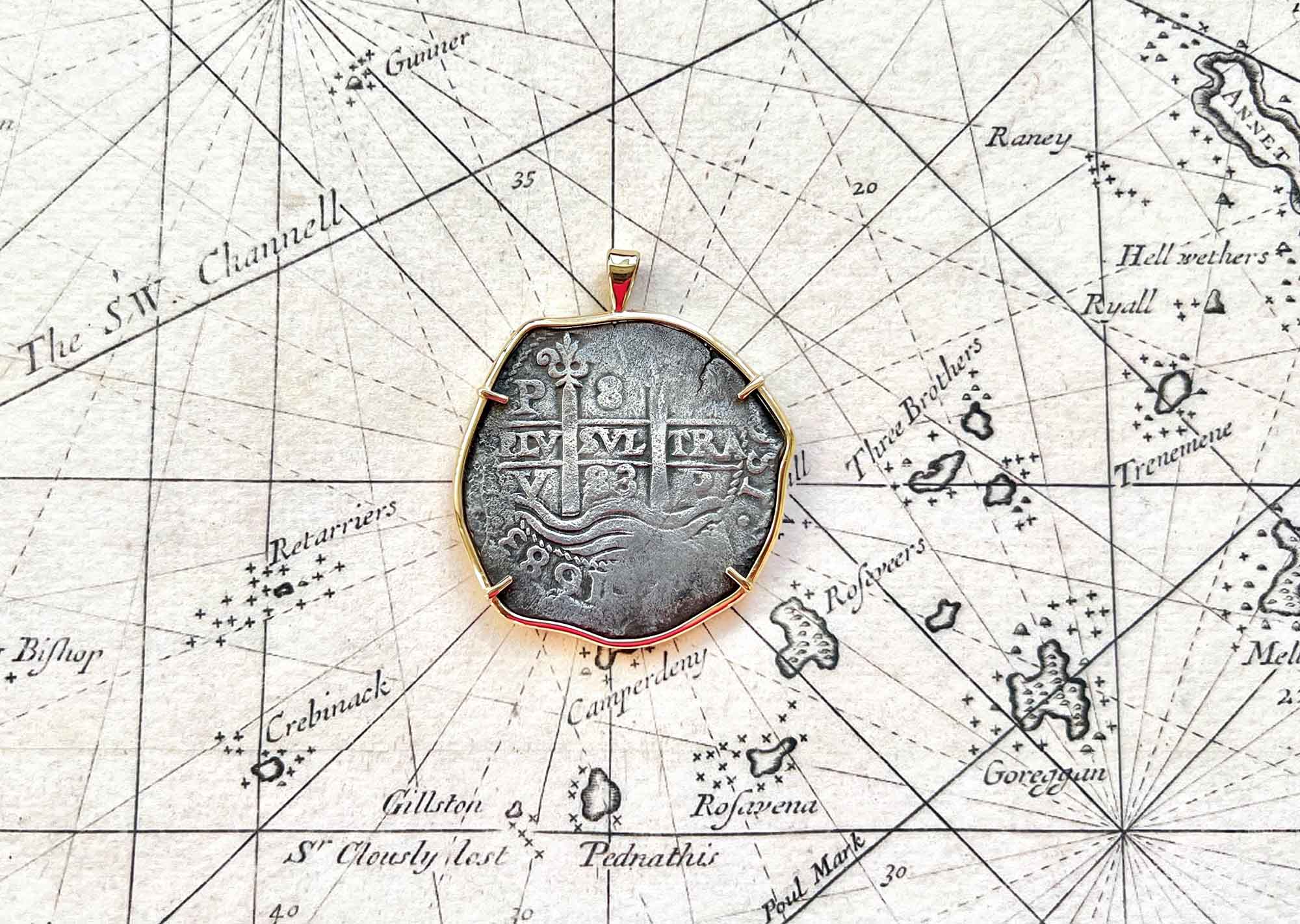

How to ‘read’ a Piece of Eight

Obverse

Usually non-existent on regular coins, around the outside is POTOSI – ANO – 1682 – PERU.

The two upright ‘pillars’ represent the Pillars of Hercules, and the waves below them the Atlantic Ocean.

Starting in the 10 o’clock position there’s a ‘P’ for Potosi, next is the 8 for the denomination of 8 reales (pronounced ‘ray-al’).

Next is the assayer’s initial ‘V’ for assayer Pedro de Villar, who ran the mint from 1679 to 1697. The other ‘V’ means the same.

The numerals ‘82’ (meaning date 1682) are between the Pillars at the crest of the wave.

Through the centre runs the phrase PLV SVL TRA – plus ultra, meaning more beyond the Pillars of Hercules.

Reverse

Usually non-existent on regular coins, around the outside is CAROLUS II . D . G . HISPANIA, representing Charles II by Grace of God King of Spain and the Indies.

Prominent is the crusaders cross, with lions and castles in the four quadrants, representing the early Spanish kingdoms of Leon and Castile.

At the 9 o’clock position is a ‘P’ for Potosi mint and 3 o’clock position ‘V’ for assayer Pedro de Villar.

At the bottom of the cross is also the date ‘82’, for 1682.

More information can be found here: https://cannonbeachtreasure.com/blogs/news/how-to-read-a-spanish-piece-of-8-pillars-waves-edition

Pendant Coins

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1701 (the latest date piece of eight found on Association, adding to speculation that these were captured at Vigo Bay in 1702) and acquired directly from salvor Roland Morris many years ago. Lima mint, assayer H. As they go this is a nice example with clear heavy strike. Very little corrosion on the pillars and waves side, mild corrosion on the cross side. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 32g, measures 37mm at widest (left to right).

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1690, date clear on both sides. Potosi mint, assayer VR (Pedro de Villar). A very nice and interesting example, acquired directly from salvor Roland Morris many years ago. No corrosion, so would’ve been protected within a ‘clump’ of coins. Right side of coin clearly shows two neat restrikes, which only adds to this coin’s uniqueness and fascination. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 31g, measures 39mm at widest (top to bottom).

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1689. Lima mint, assayer R. This is an extremely nice example indeed, with clear heavy strike on both sides, three dates visible, which is very rare. On the cross side the date at the bottom appears to show 68 for 1668, but in fact it’s three numerals, the right-hand one partly obscured, and actually says 689 for 1689. It’s unknown why some years the coins had just the last two numerals and others the last three. This coin makes a very fine pendant indeed. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 33g, measures 41mm. OUT OF STOCK

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 169?, last numeral unclear, although the Lima V assayer (Francisco Villegas) was between 1684 and 1693 – the last digit has a loop at top, so it must either be from 1690, 1692 or 1693. This coin was recovered in 1974 from within the clump pictured here. A very nice attractive example with no corrosion. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 34g, measures 37mm at widest (left to right). Pictures show the salvors, Don Bates and Terry Hiron with the clump of coins, which were all pieces of eight.

Association 1707: 8 Reales, 1683, with three clear dates – twice on pillars and waves side and once on cross side, which is extremely rare indeed. Potosi mint, assayer V. An exceptionally attractive example of the pillars side, showing clear detail and with the full 1683 date around the perimeter – it is very rare and desirable to find one with three dates visible. The pillars side shows light corrosion, but the cross side has more pronounced corrosion, although actually it’s quite attractive, telling of its history beneath the sea. Acquired directly from salvor Roland Morris many years ago, this coin would have been part of a clump, with the pillars side protected inwards, and the cross side unprotected from the effect of the sea on the outside. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 28g, measures 39mm all round.

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1686. Potosi mint, assayer VR. An exceptional example with no corrosion, so probably protected within a clump. Both sides with sharp heavy strike and clear dates. On the cross side the date at the bottom has been double struck, appearing to show 88, but if one looks carefully its 86 twice. This coin makes a very fine pendant indeed. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 38g, measures 39mm.

Hollandia 1743: 8 Reales, pillar dollar of 1741, Mexico mint. These coins superseded the hand struck cob pieces of eight and were milled coins produced using a screw press. Surely one of the most attractive coins ever created, both sides are beautifully designed. This is an exceptionally fine example which would’ve been uncirculated when it went to the bottom of the sea in 1743. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. Weight 33g, measures 38mm. The Hollandia was a Dutch East Indiaman on her maiden voyage when due to poor weather and a navigational error she hit the Gunner Rock off the Isles of Scilly on the night of 13 July 1743.

Non wreck coin: Acquired because it’s a lovely design of coin and from the reign of Queen Elizabeth the First, a fascinating period. It is a silver shilling in extremely good, almost uncirculated, condition – a ‘hammered’ coin, so hand stamped between two dies. It’s not dated, but the ‘A’ mintmark (the kind of ribbon mark above the Queen’s head) reveals it was struck in either 1582, 1583 or 1584 at the Tower of London mint. The silver has a lovely dark patina of age to it, especially on the coat of arms side. Fitted with 18ct gold bezel and loop. A smaller and much lighter coin, it measures 34mm across and weighs just 8g.

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1694, Potosi mint, assayer VR (Pedro de Villar). Quite a corroded example, so would’ve been exposed to the ravages of the sea for over 250 years. The pillars, 8 (for 8 reales) and date (94) are clear. Mint isn’t visible, but VR is, meaning Potosi. Also, the waves at the bottom go up between the pillars for Potosi (it was high in the mountains) and down for Lima (low down). Fitted with sterling silver bezel and loop. Weight 25g, measures 37mm all round.

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1686, Potosi mint, assayer VR (Pedro de Villar). A nice clear example with no corrosion, so would’ve been part of a clump and protected. Both sides show evidence of double, or possibly even treble strike. Bezel made to order. Weight 27g (correct weight for a piece of eight).

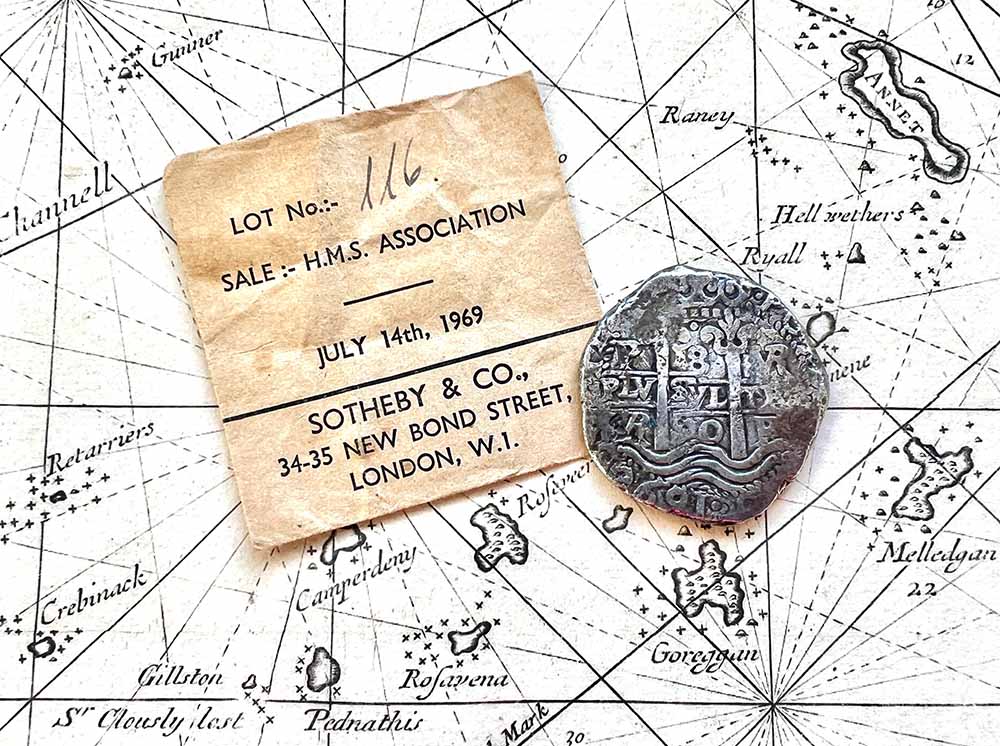

Association 1707: 8 Reales, dated 1690, Potosi mint, assayer VR (Pedro de Villar). A nice clear example with central stamping and no corrosion, so would’ve been part of a clump and protected. Pillars side is especially clear and attractive, with date showing around the outside, which is very rare. Cross side less clear and shows evidence of double strike. Comes with original little Sotheby’s lot number envelope from 1969 auction, so this coin must have been an early recovery from Association. Bezel made to order. Weight 24g and measures 38mm at widest (top to bottom).

‘Rill Cove Wreck’ Circa 1618: This is an earlier style of piece of eight, or 8 reales, dating to Phillip III of Spain, recovered from the ‘Rill Cove Wreck’, otherwise known as ‘Lizard Silver Wreck’, located west of Kynance Cove on the Lizard peninsula of Cornwall. The wreck’s identity has remained a mystery to this day, although it was probably an armed merchantman that sank around 1618, as apparently some salvage work commenced in that year. Coins from this wreck are generally in poor condition due to abrasion from shifting sands and shallow depth, this example actually being better than many. No date, mint, or assayer visible, but probably Seville mint. At five o’clock on the shield side III can be seen, for Phillip III of Spain. The corrosion on this coin and light and dark areas gives it great character, and it would look amazing with a contoured gold bezel around it. Bezel made to order. Weight 17g (so 10g less than minted), measures 36mm.

Non wreck coin: Acquired because it’s a very attractive coin and dated 1588, the year of the iconic Spanish Armada. It is also a finely produced and very clear coin, almost in uncirculated condition. These coins, similarly to the pieces of eight, were hand hammered, but obviously with rather more care! It is a one philipsdalder, or ‘thaler’, of Philip II of Spain, from the Antwerp mint. Bezel made to order. Measures 40mm across and weighs 34g.

Hollandia 1743: Silver Ducaton (Silver Rider) from Utrecht mint, Netherlands, dated 1742. An extremely attractive and very fine example of this quite large coin, which would’ve been uncirculated when it went to the bottom of the sea in 1743. Bezel made to order. Weight 32g, measures 41mm. The Hollandia was a Dutch East Indiaman on her maiden voyage when due to poor weather and a navigational error she hit the Gunner Rock off the Isles of Scilly on the night of 13 July 1743.